What is Prolapse?

A prolapse occurs when pelvic organs such as the bladder, uterus or rectum push into the vaginal space. A prolapse can occur in one or more of these areas. Over time you may notice a bulge coming out of the vagina, or in the case of a rectal prolapse, coming out the anus. [1]

Types of Prolapse:

There are 4 main types of prolapse. The first 3 occur only in women. The 4thcan occur in both men and women.

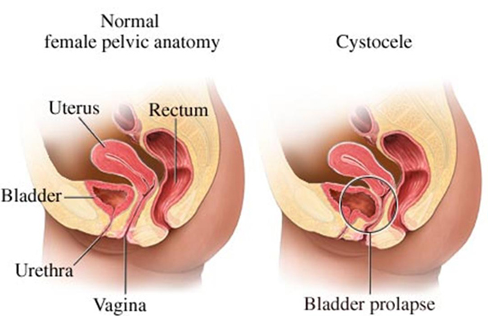

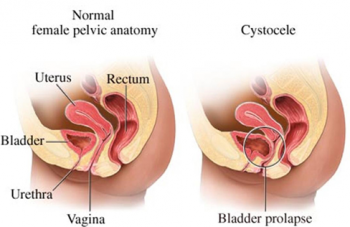

Anterior Vaginal Wall or Cystocele Prolapse

An anterior vaginal wall prolapse is sometimes referred to as a cystocele. It occurs when the structures in front of the vagina, such as the bladder, push into the vaginal space. [2] [3]

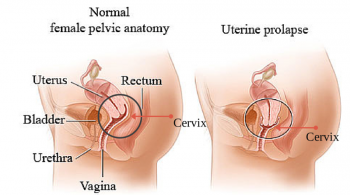

Apical Prolapse

An apical prolapse is sometimes referred to as a uterine or uterovaginal prolapse. It occurs when the structures at the top of the vagina, such as the uterus and cervix, come down into the vaginal space. Following a hysterectomy the top of the vagina, called the vaginal vault, may descend into the vaginal space. This may be referred to as a vaginal vault prolapse. [2] [3]

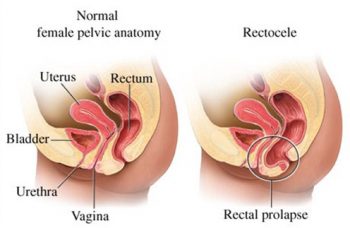

Posterior Vaginal Wall Prolapse

A posterior vaginal wall prolapse is sometimes referred to as a rectocele. It occurs when the structures behind the vagina, such as the rectum, push into the vaginal space. [2] [4]

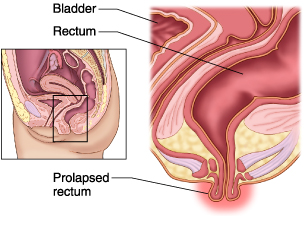

Rectal Prolapse

A rectal prolapse occurs when the rectum comes out of the anus. This can occur in both men and women.

While a gynecologist or urogynecologist will often see you for a posterior, apical or anterior vaginal prolapse, a rectal prolapse is usually seen by a colorectal surgeon. Pelvic physiotherapists treat all 4 types of prolapse.

Causes of prolapse:

A prolapse occurs when the support structures for the pelvic organs and the pelvic floor muscles can no longer adequately support the pelvic organs [4]. Pregnancy and childbirth can weaken the pelvic floor and decrease pelvic organ support. This effect increases with more pregnancies, use of forceps, larger babies and prolonged labour. [3]

Increased abdominal pressure can be a contributing factor to prolapse. These can include chronic coughing, chronic constipation, obesity, and repeated heavy lifting [2].

Connective tissue disorders, such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, can predispose you to prolapse. In these disorders the connective tissues that support the pelvic organs are not as strong and are not able to provide adequate support over time. [2]

Who experiences prolapse?

A prolapse is more common in women who have had one or more vaginal deliveries, but it can also occur in women who have had C-sections or have never been pregnant. Prolapse may occur in women postpartum, either soon after childbirth or when returning to exercise.

Another common time for women to notice a prolapse is around or after menopause. The pelvic floor muscles, pelvic organs and associated connective tissues are sensitive to estrogen. As estrogen levels decrease around menopause, support for pelvic organs decreases, increasing the likelihood of prolapse [5].

Risk factors for prolapse

- Chronic cough

- Chronic constipation

- Vaginal delivery

- Prolonged labour

- Instrumental delivery (forceps or vacuum)

- Number of pregnancies

- Obesity

- Repeated heavy lifting and/or straining

- Aging and menopause

- Family history of prolapse

- Connective tissue disorder (eg. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) [2]

Symptoms of Prolapse

A minor prolapse most often occurs without symptoms. It may only be noticed by your doctor. A prolapse that is more progressed may have symptoms such as a vaginal bulge, or feelings of pressure or things will fall out of the vagina. A prolapse generally does not cause pain. Prolapse symptoms generally vary with coughing, lifting and other activities. They will often vary based on time of day, and may also vary with bowel and bladder filling. Women with prolapse may experience difficulty emptying the bladder due to kinking of the urethra, or difficulty passing bowel movements due to a prolapse. [2]

Women with prolapse may also experience other pelvic floor concerns such as:

- Stress urinary incontinence

- Overactive bladder

- Fecal incontinence

How is prolapse diagnosed?

A prolapse will generally be diagnosed by your family doctor, gynecologist, urogynecologist or pelvic floor physiotherapist. Generally it is diagnosed by vaginal exam. Your doctor or physiotherapist will generally ask you to bear down as they note how far different parts of the vagina descend.

How to prepare for your appointment

If you are being assessed for a suspected prolapse, whether you are seeing your family doctor, a physiotherapist or a specialist, you should expect to have a vaginal exam. In addition, you will be asked about the extent of your symptoms. Questions you may be asked may include:

- Is there a bulge out of the vagina?

- If so, is it there all the time or does it come and go?

- What types of things aggravate the prolapse?

- Are there any bladder symptoms such as:

- Urgency or frequency?

- Leaking with urgency?

- Leaking with cough, sneeze or activity?

- Do you have any issues emptying your bladder or your bowels?

- Do you get regular periods, are you approaching, or have you gone through menopause?

Treatment for Prolapse:

There are multiple treatment options for pelvic organ prolapse. They may be done individually, or you may use a combination of these options.

Wait and Observe

The first is to wait and observe. This is generally done in women who do not notice their prolapse. They may progress to further treatment options if their prolapse progresses.

Pelvic Floor Exercises and Physiotherapy

The second treatment option is pelvic floor muscle exercises with or without training and supervision by a pelvic floor physiotherapist. A pelvic floor physio will also often address constipation. She will also give you guidance and modifications to your regular (non-pelvic floor) exercise routine as needed to allow you to keep active without aggravating your prolapse. She will also help you to address any other symptoms related to pelvic floor disfunction such as urinary or fecal incontinence, constipation, pelvic or sexual pain, and overactive bladder symptoms.

Pessary

Another treatment option is the use of a pessary. This is often done in conjunction with pelvic floor muscle training and/or pelvic floor physiotherapy. A pessary is a device that is inserted into the vagina to support a prolapse. There are many different types and shapes of pessaries. They are fitted by a doctor, usually a gynecologist or urogynecologist, though some pelvic floor physiotherapists have training in fitting pessaries. Some pessaries require a doctor to remove and clean them periodically, while others can be removed and reinserted by the individual. Some types of pessary allow you to have sex while the pessary is in, while others need to be removed first. Return to your doctor if you have pain, bleeding or your pessary does not stay in place. You may need a different size or type of pessary. [3]

Vaginal Estrogen

Vaginal Estrogen cream or tablets are often used in women who have gone through menopause. They can help improve health and strength of the vaginal tissue, and may help in combination with a pessary or pelvic floor muscle training. [3]

Surgery

The final treatment option is surgery. This is the most invasive treatment option, and is generally considered if a prolapse is not manageable with a combination of the previous options. As with any operation, there are risks. Your surgeon will go through these with you. Some side effects may include:

- Stress urinary incontinence which is unmasked by correcting the prolapse[2]

- Worsening urinary urgency and/or frequency

- Pain

There are different types of surgeries that your gynecologist or urogynecologist may choose for your prolapse. These will depend on many factors. Possible surgeries may include a hysterectomy, vaginal repair, colpocleisis (closing off the vagina) or a surgery to lift and attach your vagina or uterus to a ligament or bone (such as sacrocolpopexy or sacrospinous fixation). Your surgeon may also recommend a combination of theses factors. Colpocleisis is generally only recommended in women with other failed prolapse surgeries, in poor health, who no longer wish to be sexually active as vaginal intercourse is no longer possible following this surgery. [3]

Following surgery you may have to restrict your activities for a period of time or long-term. Ask your surgeon if this will be the case with you. You should also ask how long you should expect to take off work, what the success rate is and how likely it will be that you will have a recurrence of your prolapse. Pregnancy is generally not recommended following a prolapse repair surgery.

What can I do myself to help my prolapse?

Addressing your aggravating factors can help to decrease the effects of a prolapse. This may include losing weight, addressing a chronic cough (which may include quitting smoking), or addressing constipation. [3]

References:

- International Urogynecology Association, “Pelvic Organ Prolapse,” 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.yourpelvicfloor.org/media/Pelvic_Organ_Prolapse.pdf. [Accessed 17 May 2018].

- C. B. Iglesia and K. R. Smithling, “Pelvic Organ Prolapse,” Am Fam Physician, vol. 96, no. 3, pp. 179-185, 2017.

- Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists, “Pelvic Organ Prolapse,” 22 March 2013. [Online]. Available: https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/patients/patient-information-leaflets/gynaecology/pi-pelvic-organ-prolapse.pdf. [Accessed 28 May 2018].

- C. Percu, C. Chapple, V. Cauni, S. Gutue and P. Geavlete, “Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System (POP–Q) – a new era in pelvic prolapse staging,” J Med Life, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 75-81, 2011.

- T. Tzur, D. Yohai and A. Weintraub, “The role of local estrogen therapy in the management of pelvic floor disorders,” CLIMACTERIC, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 162-171, 2016.